- Home

- Vicki Hastrich

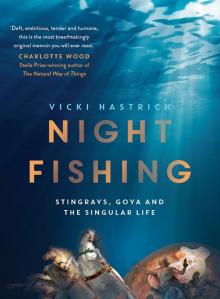

Night Fishing

Night Fishing Read online

Praise for Night Fishing

‘In this “natural history” of the author herself, we travel gently through childhood and family, grief, love and solitude—and her spellbinding twin obsessions with art and the natural world. It is the work of a questing, roving intellect and a rare humility, and Hastrich’s sheer joy in language infuses the whole with a deliciously sly, intelligent humour. I’d liken her to an antipodean Annie Dillard with a fishing rod in one hand and the whole of western art history in the other—except there simply is no other writer like Hastrich. This book will tell you things you never knew about your world and yourself, and you will never forget it.’

Charlotte Wood, author of The Natural Way of Things

‘I read Night Fishing in one greedy gulp, marvelling at its intelligence, humour, beauty and wonder. Immediately I’d finished, I began again, reading each meticulous essay with care, taking my time, wanting—needing—to attend to the words in the way that Vicki Hastrich attends to her world. She sees every overlooked detail. She listens for the quiet thrum under the everyday. She invites us, via great art or small fish, into the depths of her remarkable and unique world view. Her personal vision is both intimate and epic. Every essay relates an episode observed and considered with writerly precision and delicacy. Night Fishing is a unique memoir from a powerful, tender and insightful writer. It’s the book I want everyone I love to read. It’s a book I will never let go. Vicki Hastrich depicts a life lived with eyes and mind wide open. She even made me want to go fishing!’

Ailsa Piper, co-author of The Attachment

‘Loved this—a gentle, meditative surge, a memoir which never strays too far from that big collective unconscious, the sea. Here the sea is night-fear, is stumps in the water mistaken for doughty swimmers, is secrecy, is revelation. On the journey, there are pearls—a mother doing crosswords in an austere billiard table showroom, and so passing the ocean of words to her daughter; the numbfish, a death harbinger; Galileo painting the waxing and waning moon as the world’s water heaves from its pull; Dasyatis brevicaudata caught in the Garden Island graving dock, destined to glide out their graceful days in the Taronga Park Aquarium. And childhood, the most sparkling and scary sea of all.’

@tomsbooks

Praise for The Great Arch

‘I gulped down The Great Arch in two long sittings, cancelling a coffee date because I didn’t want to put it down. Hastrich had me hooked from the opening pages … I feel like climbing the bridge and yelling out how good it is.’

Christos Tsiolkas, author of The Slap

‘… a story of imagination, loneliness, obsession and love … A deeply tender, very funny and sad and beautiful book.’

Charlotte Wood, author of The Children

‘… as airy, soaring and magnificent as the bridge itself.’

Michelle de Kretser, author of The Lost Dog

Praise for Swimming with the Jellyfish

‘Seemingly effortless, completely endearing, this novel is an absolute joy.’

Debra Adelaide, The Sydney Morning Herald

‘… dazzling in its surprising juxtapositions of human types and in its colloquial flashes …’

Michael Sharkey, The Australian

‘A deceptively clever first novel.’

Ian McFarlane, The Canberra Times

VICKI HASTRICH is a Sydney writer. She started out with the ABC as a TV camera operator and became an assistant director in drama. When she began writing, a range of jobs followed, including warehouse hand, picture researcher, factory worker, archivist and oral historian. Along the way she picked up a Doctor of Arts degree from the University of Sydney. Her two novels, Swimming with the Jellyfish and The Great Arch, were published in 2001 and 2008 respectively. She has recently turned to non-fiction. ‘Things Seen’, a cornerstone essay in Night Fishing, was first published in The Best Australian Essays 2016.

First published in 2019

Copyright © Vicki Hastrich 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to the Copyright Agency (Australia) under the Act.

pp. 56 and 57: A Bigger Message: Conversations with David Hockney by Martin Gayford, text © 2011 Martin Gayford. Printed by kind permission of Thames & Hudson Ltd, London.

pp. 233, 236 and 237: ‘A kind of sharing’ from Keeping a Rendezvous © John Berger 1992, and John Berger Estate.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Email: [email protected]

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

ISBN 978 1 76087 550 3

eISBN 978 1 76087 121 0

Set by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Cover design: Christabella Designs

Cover photos: Quentin Houyoux/Getty (water); Bildarchiv Monheim GmbH/Alamy (Giovanni Battista Tiepolo)

For Di

We’re going to Woy Woy.

‘… the sea is the first home of the mind …’

Peter Godfrey-Smith, Other Minds

Contents

The Hole

Things Seen

My Life and the Frame

From the Deep, it Comes

The Tomb of Human Curiosity

Amateur Hour at the Broken Heart Welding Shop

The Boat Show

Night Fishing

The Nature of Words

The Butcher and the Housekeeper

The History of Lawn Mowing

Self-portraits

Bucket of Fish

Acknowledgements

The Hole

I learnt the word ‘trespass’ at an early age. Not from Sunday school, although I heard it there—forgive us our trespasses—but from signs hung on oyster leases.

Trespassers will be prosecuted.

In my head this meant they would be shot. Crazy Shackleton had a gun and we believed he’d use it. Reach a hand in through the watery fence line of any of the leases he farmed and he’d blow your head off.

Shackleton lived in a closed-up cottage behind a rank wall of lantana and morning glory. Angry dogs to match their angry master barked from somewhere out the back but were never seen. Shackleton was not much seen himself—at least by me. But those signs were everywhere. Also: Keep out. Some were hand-painted and some stencilled, but whether the lettering was industrial or mad and fierce, they fairly screamed: Mine, mine.

Somehow they made the place even better. And, oh God, that place was good.

We went to this spot on the New South Wales Central Coast on semi-regular holidays with my parents’ best friends and their three children. Uncle Clive and Aunty Pam, as they were to us, co-owned the house with Clive’s sister-in-law. His mother had bought the water-access-only house on the Brisbane Water estuary in the 1930s. It was four rooms, had no electricity or running water, and was furnished with stuff that would already have been old in the thirties, a few key pieces of which were particularly alluring to us kids: a gramophone player the size of a fridge and six records, five of which we broke; a piano, out of tune, with hinged brass candlesticks that folded out either side of a music ledge; and a medicine cabinet full of strange little jars and bottles—ipecac, gentian violet and ointments ancient enough to have come from a pharaoh’s to

mb, all of it probably lethal. There were many kerosene lamps of various shapes and sizes on a shelf in the kitchen; on the same shelf was an alarm clock made out of a tuna tin. In the front room there were holes in the floorboards that one could lie down beside and put an eye to; dark shapes in the gloom included that of a claw-footed bath. Thankfully we washed in a big enamelled basin placed on the kitchen floor, because the idea of bathing in the dark under the house was beyond terrifying.

No one would do it nowadays—take six kids, food, ice and pets (including, once, a labrador with ten puppies and our mean cat) across the water in a hired putt-putt boat, haul the lot up a rough track to a dilapidated cottage on a hill, there to lie on kapok mattresses and poo on a can dunny while batting off pterodactyl-sized mozzies—and call it fun. Probably nobody else did it much then either; after all, it was the swinging sixties and Australia was getting modern.

I loved it. We all did. But I really loved it.

I was the youngest child in our family and I remember, before I even went to school, trailing around behind my mum as she did the housework in our nice new suburban home, plaintively, pathetically, whining, ‘When are we going to Woy Woy?’ That was the catch-all name we gave to the area and you can imagine how well those two syllables lent themselves to being drawn out by a whingey kid. I felt I was being unfairly kept away from my rightful life. I should live there. I might consent to go to school when the time came, if I could go by ferry.

Most mornings up there, the dads took the kids fishing in the boat; that is, after enough swearing and pulling on the leather strap cranked the flywheel and the engine finally started. At Easter time, when we always holidayed, the autumn season and all it implied combined at high tide to make the waterways seem especially slow and serious. Sound travelled. We took the shortcut ‘roads’ marked with sticks and slipped between the oyster leases into Rileys Bay. Brimful and eerie. Cormorants sat on lease poles holding wings out to dry. At Rileys the bush came down to the water, mangroves in one corner and in the trees behind, bellbirds. A poor weatherboard house sat above a little sandy beach at which we kids often swam, having first negotiated the track past Shackleton’s. Grazing on a small patch of open ground beside the house was a cow, which I believe to this day was deaf, although my brother Roger, a thoughtful man who is not by nature argumentative, disputes this fact. ‘How could you know?’ I just do. It occasionally bellowed, so it wasn’t mute as well. Also in that corner, on those tide-muffled mornings, there would always be one crow calling out like an old woman complaining about a pain in her side.

Rileys was a nursery for fish. Ten cents for the first fish in the boat was a big incentive (decimal currency came in when I was six). Twenty cents for the first of edible size. Better fish sometimes came up out of the water: whiting, flounder, a bigger bream among the million babies.

The dads were patient, especially considering that in those days they hardly ever had us on their own. They untangled lines, helped get fish off hooks and dealt with snags, though we were taught to be self-sufficient. The many little bites kept us busy, but if I did get tired there were always fish to play with. I squeezed trumpeters to make them croak (gold-, brown- and silver-striped, you caught them drifting over weed), and in the bottom of the boat—in the gutter that held the bilge water—I gave swimming lessons to little bream, steering them up and down.

If it was windy we went instead to anchor in a bay back near our wharf—Purple Pumpernickel Bay we called it, after an ugly purple-painted steel yacht that was moored there. The water was deep there, dropping off close to shore. Its brooding emerald looked promising but it only ever delivered pesky babies.

In the afternoons, we seemed to be entirely free to go wherever we pleased, unsupervised. We racketed around the bush tracks or fished off the wharf while the dads took the boat out again for adult fishing time in a deep, deep spot which was hard to find (but when found was a piscatorial pot of gold); a secret place of mystery and many stories that was called … the Hole.

The Hole was situated quite nearby, and close to where the estuary narrowed. The greater part of the estuary filled and emptied through this neck, so the tidal forces were huge; indeed, the area was and is ominously known as the Rip.

The Hole, gouged out over millennia, could only be fished at the top or bottom of the tide, when the water slowed sufficiently that lines could reach the bottom and the big fish that lurked there could feed. Anything might come up from that extraordinary spot: red emperors, giant flathead, sharks—or nothing. Almighty tangles might ensue; the dads fished with cork handlines, and the swirling water was never completely still. Although what did we kids really know? We never went there.

While we waited for the dads to return we hung around the wharf. Sometimes we did take oysters, but not from leases, just ones on rocks in the shallows nearby, which we smashed open to use for bait when we ran out of prawns. We squeezed beads of pop-weed at each other; we tried to net mullet, those nervy vegetarians who would not take our hooks; we lay down on the old wharf timbers and hung our heads over the edge. I spent hours looking. At the mullet, the jellies, the sunlight ladders, the eddies. At toadfish going about their obsequious snooping.

When the putt-putt returned, the dads would sling us a wet sack if they’d had luck, and while they moored we ran on ahead with it to show the mothers. By then, with all jobs finally done, the women might be in the front room knitting. The front room was lined with beds around the walls—there was no lounge room. My bed was against the window, and in the mornings I woke before everyone else and looked out to early boats on the water, and to the houses and jetties on the opposite shore, which at that hour were gold-buttered.

The mothers did not seem to mind the wet sack on the floor, and we exclaimed together at what came out: the impressive ugliness of a dusky flathead; a snapper, its shining pink flanks glorious with aqua speckles. We always hoped for a jewfish, something to which Uncle Clive especially aspired but that I never saw him get. The sort of jewfish he plotted for would not fit in the sack.

At night, tucked in bed and daubed with calamine lotion, we listened to the parents having a few beers in the kitchen and playing cards; the cheerful noise of friends.

And then, not long after I turned eight, the news came that it was over.

•

I like to think I first went up to Woy Woy before I was born, when I was just a peanut-sized embryo in an ocean of my own. I don’t know if that’s true, and Mum and Dad are gone—Dad when I was 21—so I can’t ask them now. But I don’t see why that wouldn’t have been so; I’m the youngest and my parents would have holidayed up there many times before having me. Out of all our visits, there are maybe half a dozen photos. In the earliest I’m about eighteen months old. There are ten of us in the boat, and I’m standing, leaning against my father’s knee as he holds the tiller. (I remember now the way the tiller and rudder hooked on the back of the boat, the attaching mechanism so simple, a couple of metal spigots that dropped into collars. Why would I have observed such a thing so closely?) In that photo, it looks like we are going home.

Zero to eight. And then the big announcement. We were moving interstate.

It would be fun, we were told. An adventure. This time we would live only a short drive away from the water: Melbourne’s Port Phillip Bay. We could go swimming often. We would get a boat of our own and we’d go fishing.

It did not take long for The Big Lie to be exposed. On the drive down to our new suburb on the Mornington Peninsula my parents made a poor choice in terms of public relations and took the back road, although in retrospect I suppose it didn’t matter. The alternative, Beach Road, when I finally saw it, was not scenic by any standard I had known.

Through the car window the passing landscape was flat, flat, flat. Overcast skies, nondescript suburbs, light industrial; in open spaces the beige of wild oats. Flat, flat, flat.

This was it?

As a parental betrayal it was off the scale. Perhaps they had been replaced

by aliens.

My Woy Woy bush, the hills, the sandstone rocks, that old house, the green mysterious water. From all of that, I had been cruelly separated.

I was quiet. Maybe incapable of speech. They had me prisoner. Gazing out the car window I knew right then it would never get any better. There was only one thing to do: wait it out.

It would take years.

•

We did get a boat. I knew it was never going to be a putt-putt but thought for sure a tinnie. Dad bought the vessel from an elderly widow; it had been her husband’s pride and joy—it was a great deal, apparently. Dad went to get it and backed it down our drive. It was bondwood. In its own way it was a beautiful thing, an open boat with graceful lines and varnished up to show off the golden grain of the ply; but bondwood? How could we ever get dirtily comfortable in such a craft, to do the industrious work of fishing? Bondwood. The choice was inexplicable. An alien boat for aliens.

And so, on the dull expanse of Port Phillip Bay—with its empty horizon and featureless shores, which even the tides seemed to have deserted, so indiscernible was their range—we launched the boat and ourselves. We caught flathead. Flathead and nothing else but flathead, little sand flathead, the only interest being whether we brought up one or two at a time on our two-hook rigs. And when they’d been in the bucket for a while they exuded slime. Pull one out and a curtain of gloop hung off it. To speed up the cleaning process back at home, Dad had to invent a rack so they could be de-slimed first with a blast of the hose.

•

Finally I grew up and, after detouring via Perth, was free at last to return to the Brisbane Water. A bridge had gone up across the Rip, but thanks to patches of national park the region hadn’t changed too much. With increasing frequency I holidayed within sight of the old house, in a hamlet on the estuary from which the ocean could also be accessed. Double beauty.

Desperate to fish, I stalked the wharves and the beach to cast my rod, with haphazard results. I could not bear to fish beside other people and packed up the minute anyone came. The mere presence of even the quietest of strangers would keep me from the uninhibited level of concentration I needed if I was to get the fullest experience. The other sort of experience—just the doing, not the being—was, I thought, not worth having. In peak times this could be a major problem. I didn’t have much money and I had nowhere to keep a boat on a trailer. It was frustrating. I could see Rileys Bay and all our old haunts.

Night Fishing

Night Fishing